THE PICTURE of two trigrams: below Heaven, above Fire. The sun is high in the sky. Dry warmth of late summer, the harvest can be brought in.

What is the net of a lifetime of trial and error? How does experience live on? Man is a copycat, and also wants to be copied himself. Man is a storyteller and a listener in one. He communicates beyond his grave through his writing.

The small harvest consists of rice and apples, the big one of stories. Cumulative culture, started around the campfire, then taking the form of lines in the sand and dashes on a clay tablet, and before you know it, there are libraries and data centres. Sadly enough, the library of Alexandria has not survived - the neighbourhood library funding was cut back - in the city, bookshops are thinning out - the contents of the bookcase of the old and now deceased reader goes to the thrift shop, or straight into the dumpster with it - but look around: in unexpected places you will come across the most beautiful specimens. Books made of real paper. With smell and here and there a note and donkey ear. For example, in this green bookcase along the forest path.

Read also:

When I pass the green bookcase on my weekly bike ride along the north bank of the Vecht, it is rare that I do not dismount for a moment, and see what has been put in it the previous days.

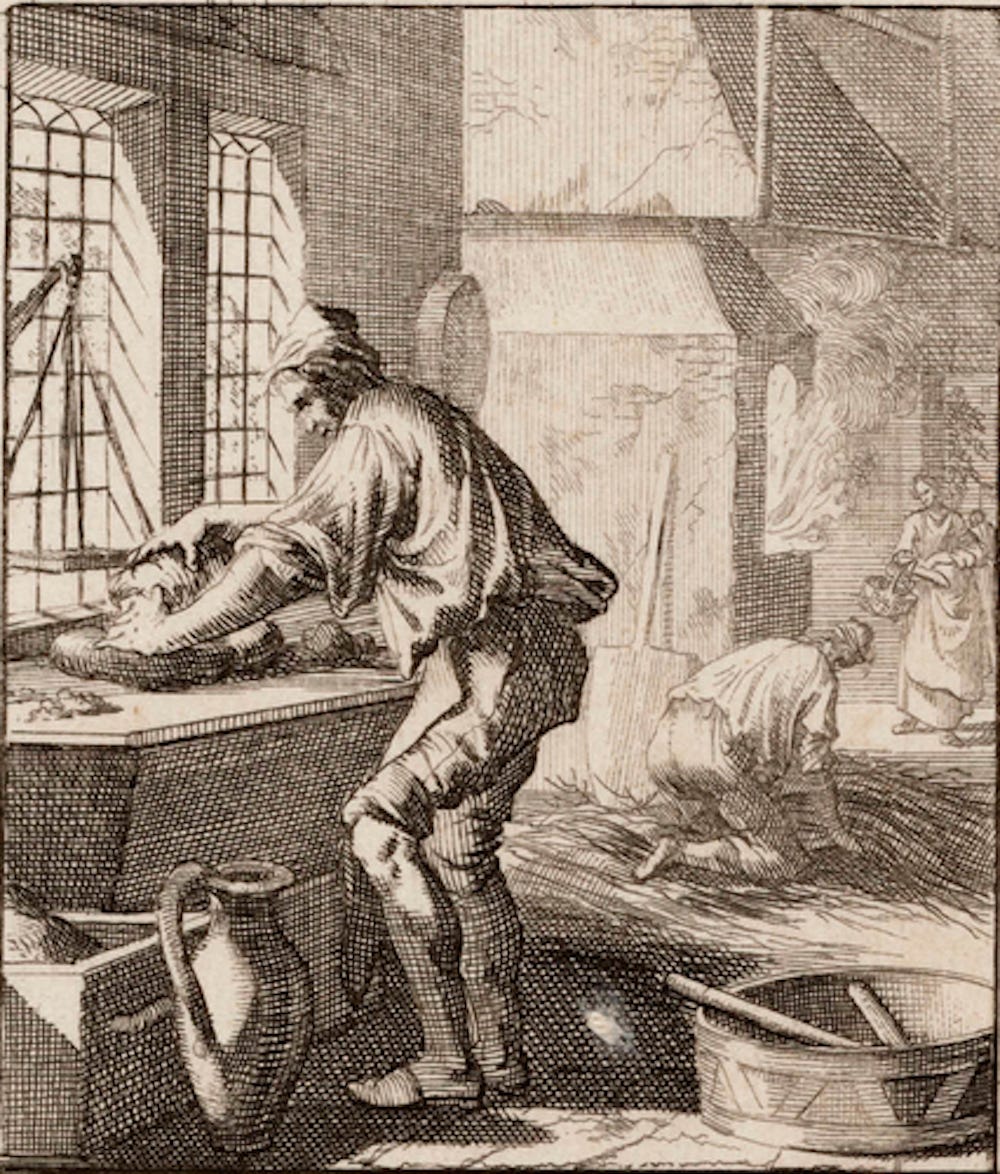

This time 'The Costume of China' was waiting for it. We had Jan and Casper Luyken as chroniclers of 17th-century crafts in the city of Amsterdam. Their 'Het Menselyk Bedryf' (‘Book of Trades’, 1694) I did not stumble upon it in the green bookcase, but a bit longer ago in a junk loft.

O Schepper van het lieve Brood

Tot voedsel van het tijd’lick leeven

Hoe heeft uw mildheidt ons genood,

Om ons u Selfs tot Brood te geeven;

O Brood dat uit den Heemel viel

Versaadigd ghy dan onse Ziel.

Het Menselyk Bedryf - Jan en Casper Luyken

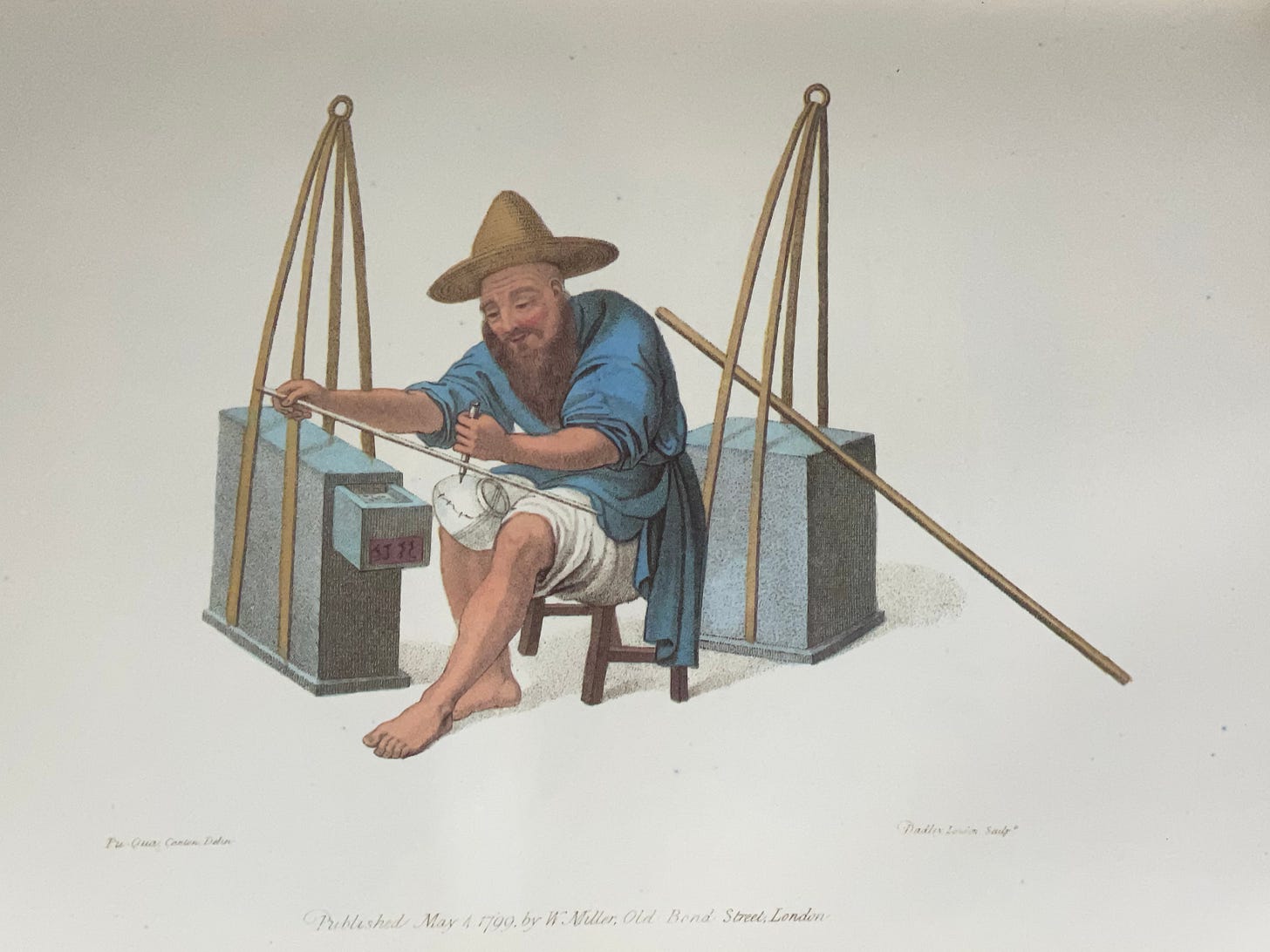

'The Costume of China' seems to be the Chinese equivalent of 'Het Menselyk Bedryf', except that it is penned by two outsiders. Some illustrations are by George Henry Mason (1770-1851), a British army officer who had visited Canton in 1789. The others are made by William Alexander (1767-1816), an English painter and illustrator. He was attached to the English trade mission in China at the end of the 18th century.

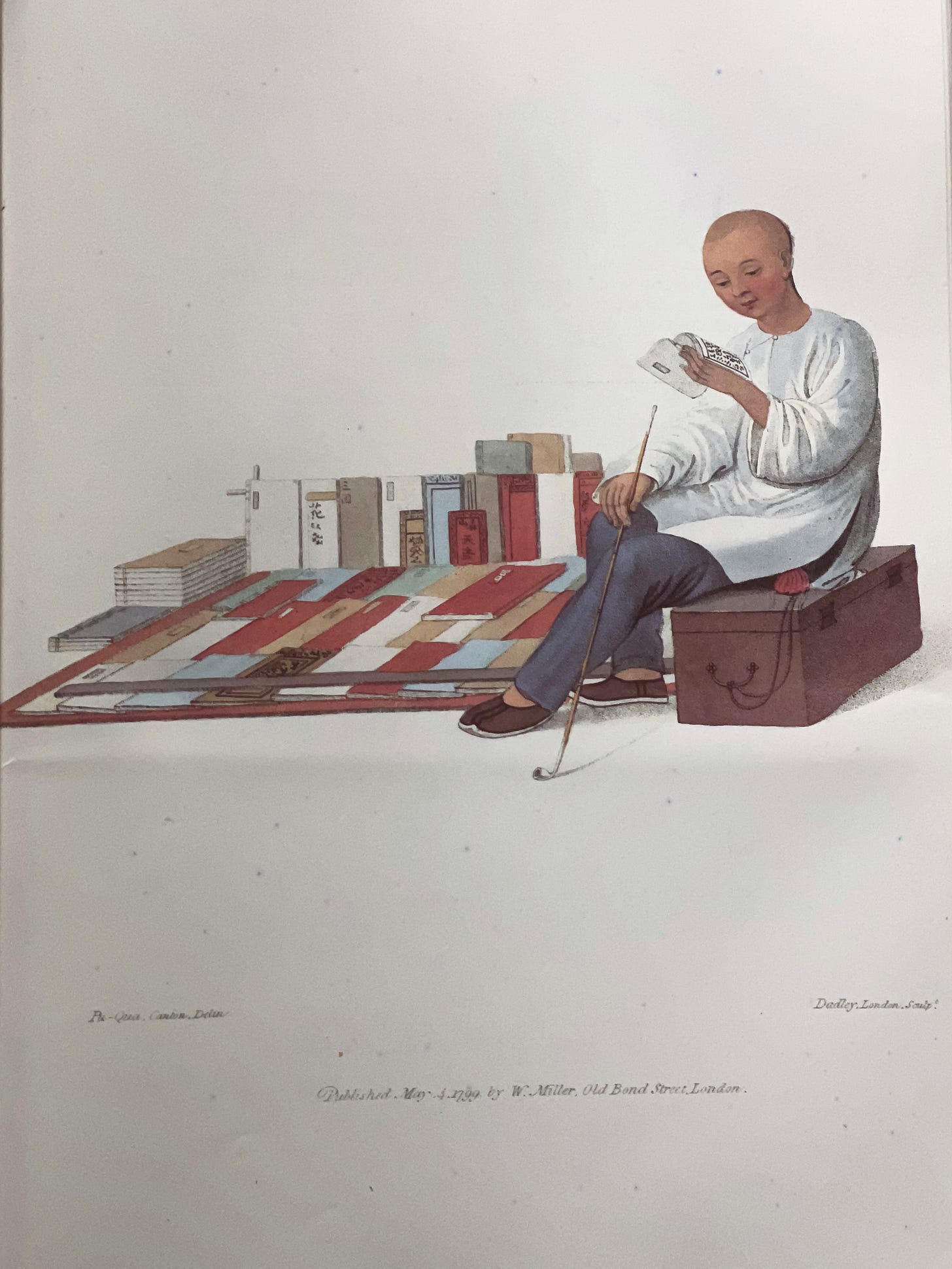

A BOOKSELLER.

The Chinese have practised the art of printing from time immemorial, but they use no press, as the Europeans do. They carve their letters upon blocks of wood; and their paper, being very thin and transparent, will bear printing only on one side: hence every leaf is doubled, the fold being at the edgeThey cover their books with a neat sort of pasteboard, of a grey colour- or else with fine satin, or flowered silk. Some are bound with red brocade, interspersed with gold and silver flowers: a manner of binding extremely neat and ornamental. Their books are lettered upon the cover. The common people have ballads and songs, inculcating chiefly the rules of civility, the relative duties of life, and the maxims of morality. The Chinese novels are amusing and instructive; they enliven the imagination without corrupting the heart, and are replete with axioms which tend to the reformation ofmanners by a powerful recommendation of the practice of virtue. Conscious that the political existence of a government depends on the proper regulation of the impulses of nature, the severest penalties are denounced by the Chinese code of laws against all publication s unfriendly to decency and good order: the purchasers of them are held in detestation by the greater part of the community; and, with the publishers, are alike obnoxious to the laws, which no rank or station, however exalted, can violate with impunity. The greatest encouragement is given by this extraordinary people to the cultivation of letters. The literati rank above the military, are all eligible ranks. to the highest stations, and receive the most profound homage from.

The Chinese has no resemblance to any other dead or living language; all others have an alphabet, the letters of which, by their various combinati ons, form syllables and words; whereas this has no alphabet, but as many characters and different figures as there are words and changes. Some of the Chinese paper is made of cotton, some of hemp; other sorts are of bamboo, of the mulberry, or of the arbutus, which latter is most in use. The inner rind being reduced by maceration and pounding to a fluid paste, is then placed in frame moulds, and the sheets are completed by drying in a sort of stove.

The ink, commonly called ‘Indian ink’ is made brought of to lamp-black beat up in a mortar with musk, and a thin size. When brought to the consistence of paste, it is put into small moulds, stamping upon the ink what characters or figures are wanted; and it is then dried in the sun or air. The Chinese do not use pens, but pencils made with hair, particularly with that of the rabbit. When they write, they have upon their table a small piece of polished marble, with a hollow at one end to contain water; into this they dip their stick of ink, and rub it upon upon the smooth part, leaning more or less heavily, to proportion the blackness. When they write, they hold the pencil perpendicularly. They write in columns, from the top of the paper to the bottom, commenci ng on the right hand side of the margin, and end their books where European s begin theirs, whose last page is with them the first. The paper, ink, pencil, and marble, are called ‘paut-see’, or ‘the four precious things’.

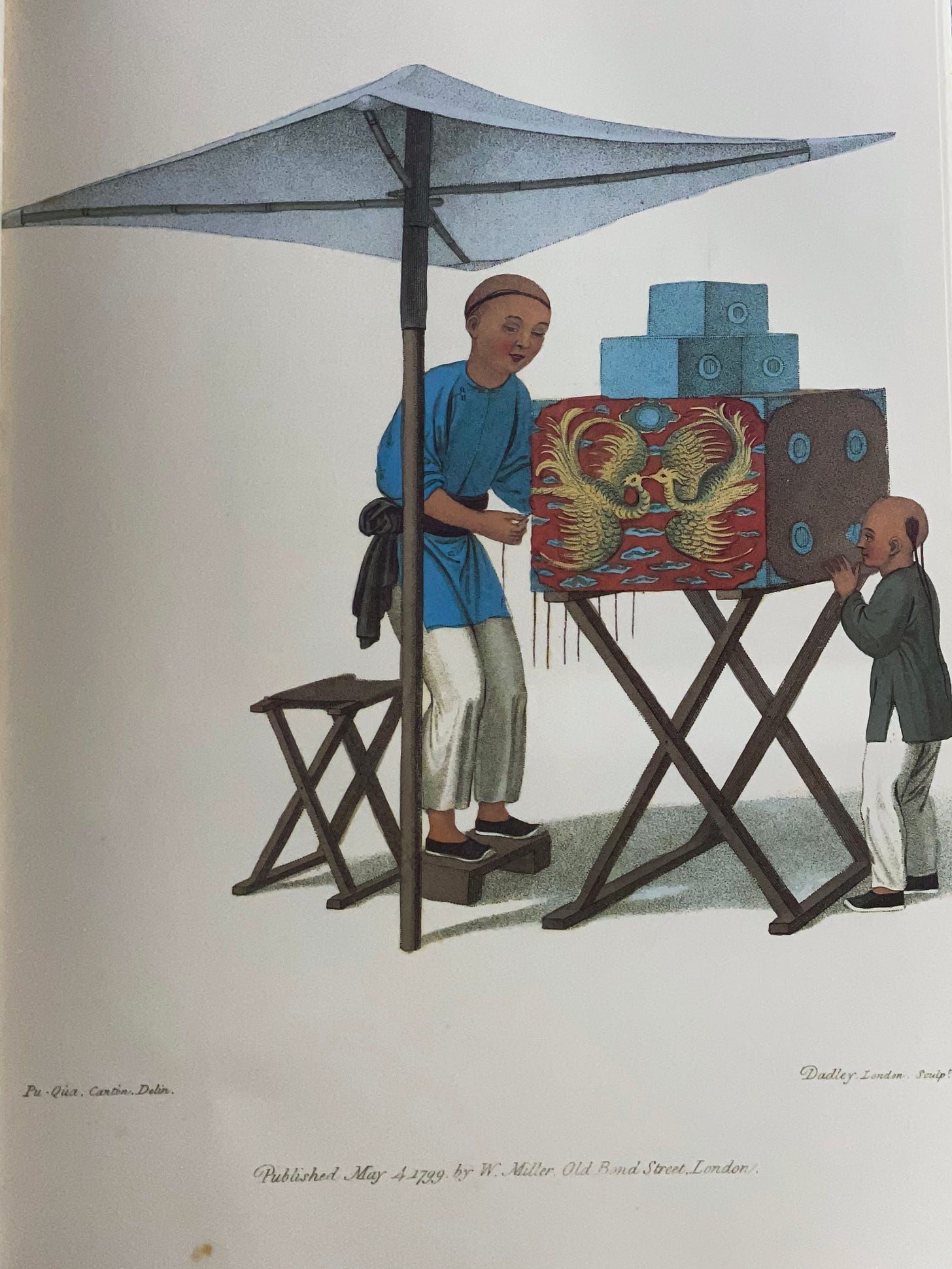

A MAN WITH A RAREE-SHOW.

Whether the Europeans borrowed the idea from the Chinese, or were the inventors of this puerile object of curiosity, cannot easily be decided; the similarity of this harmless amusement will be obvious to every one. The Chinese show-man produces a succession of pictures to the perspective glass by means of small strings, and relates a story and description of each subject as he presents it.

A MENDER OF PORCELAIN.

This ware is so common in China, that most of the ordinary utensils of the house are made of it; dishes, cups, jars, basons, flower-pots; in short, whatever serves for ornament or use.Porcelain consists, principally, of two kinds of native earth, the pètun-tsè and the kao-lin; these are reduced by water and pounding to a doughy consistency, after having been carefully freed from all impurities by repeated skimming and pouring off. The mass is then kneaded by treading, in order to prepare it for the wheel or mould, from whence, having received its form, it is taken and polished. Porcelain is varnished and baked in an oven; then being painted and gilded, it is baked a second time. The utmost attention is required in the baking, and it is not easy to regulate the proper degree of heat, since any alteration in the weather having an immediate effect on the fire, fuel, and porcelain itself, influences the process.

This old man is working with a small drill pointed by a diamond ; through the holes he introduces a very fine wire, and thus renders the bason again fit for service.

A PUPPET-SHOW.

A person mounted on a stool, and concealed as far as the ankles with a covering of blue calico, causes some very small puppets to perform a kind of play, the box at the top representing a stage. The little figures are made to move with much grace and decorum, on which account the Chinese puppet-show is rendered equally innocent as trifling, and may be presented without endangering the purity of the infant mind.

We are now living just over two hundred years later, and the book describes a vanished world. Even a good hundred years ago, many of the crafts, clothes and customs were still plentiful.

This is splendedly enhanced and colorized footage from two fragments of Benjamin Brodsky’s ten-reel film documentary, showing Peking in the 1910s. It is highly interesting material as it shows what China really was like over a century ago in 1917. It should be noted that the film was shot only about 16 years after the ending of the boxer uprising from 1899 to 1901 and 6 years after the Chinese Revolution of October 1911 during which a group of revolutionaries in southern China led a successful revolt against the Qing Dynasty. This lead to the establishment of the Republic of China which ended the imperial system.

To be continued ... and I look forward to when you leave a response, comment or idea here!