The text of this post has been translated from Dutch to English with DeepL. It will be manually edited and streamlined soon.

THE IMAGE of the two trigrams: below is a Mountain, above is Water. Mountains and rivers in all times have been a barrier to travellers, animals and plants. Even weather is often forced by mountain range or river course to take a detour.

'Water over Mountain' can be imagined as snow-capped mountain peaks. Or a mountain pass shrouded in fog, a raging mountain river or a glacier. They were the terror of every traveller. In the days of Hannibal or The Crusade in Jeans, conquering the Alpine passes was a chilling adventure. Today, you pass through the Alps in the blink of an eye. Take the Gotthard Tunnel, for example, and you drive carefree, while snacking, under the great mountain giants.

Two essential characteristics of the Water trigram are the uncertain and the dangerous. These take the form of getting lost, of avalanches, of wild animals and bandits, unpredictable weather and miscalculation. And where does the traveller find food in the barren mountains? Using the convenient tunnel may bring its own dangers, but for Dolf of Amstelveen and the Carthaginian warlord it would have been a easy choice.

From Alpine pass to river. The Vecht is loveliness itself most of the year. But in winter or early spring it can show its true face. The water level rises every day, inundates the floodplain and outer dike houses, and finally meets the dike itself. From dike to dike, a wide untamed mass of water. The sight of it humbles, for the malleability of nature turns out to be very relative. The gentle Summer Vecht shows that she has not forgotten her savage origins.

A Wild Vecht once formed a formidable barrier for those who wanted to cross her. Rightly so the accompanying text of the Obstacle hexagram gives the advice: 'in case of obstacle: go left or go right'. Perhaps crossing the river further on is easier; perhaps further on is a ford, a crossing place, a ferry, who knows, even a bridge. What pass and tunnel are to the mountains, ford and bridge are to the river country.

Before bridges were built, the river could be crossed at a ford at low water. The cowboys from Rawhide drove the herd of cattle safely through it to the other side. And hobbit Frodo narrowly escaped his pursuing black horsemen there. A ford attracted people, and in the course of time a settlement developed that grew into a village or town. Voorde - or its synonyms "trecht" and "tricht" - appear in many contemporary place names, like Maastricht, Utrecht and Amersfoort.

And then, the unsurpassed ferry. Close to the farm where we live, located directly on the Vecht dike, was at the time the ‘Kleine Veer’ or ‘Nieuw Veer’ (Small Ferry or New Ferry) later corrupted as ‘Nierveer’. New? A document mentioned it as early as 1376. Sometimes, at low tide, the river allowed itself to be waded here. But usually the ferry brought passenger and trade across. For the crossing, the ferryman had to be paid with remarkable currency: butter.

Thus, the inhabitants of Emmen had free passage (if they were on foot) over the Kleine Veer, the tenant of the ferry was then only allowed to let others pay ferry fees. For Dalfsen people this meant that every inhabitant of the kerspel Dalfsen had to pay four pounds of butter annually for ferry fees and then they were allowed to sail along a maximum of two times a day. Dalfsennet

To overcome the obstacle in the mountains, there you turn to a mountain guide or sherpa. To cross the dark unfathomable waters you do so with the help of Charon, the Hades ferryman. Or you whistle three times and request the Heen-and-Weer Wolf to bring you to the other shore. Both bring you safely across.

We are here on the banks of a mighty river

The other bank is yonder, and this one here is here

The bank we are not on is called the other side

Which then becomes this side as soon as we get there

And than this bank is called the other side, so keep that in mind

Because it's important if you need to cross

That;s quiet possible, cause there's a lot of traffic here

And that's why I keep going vice versa back and forth

The Ferry - Drs P

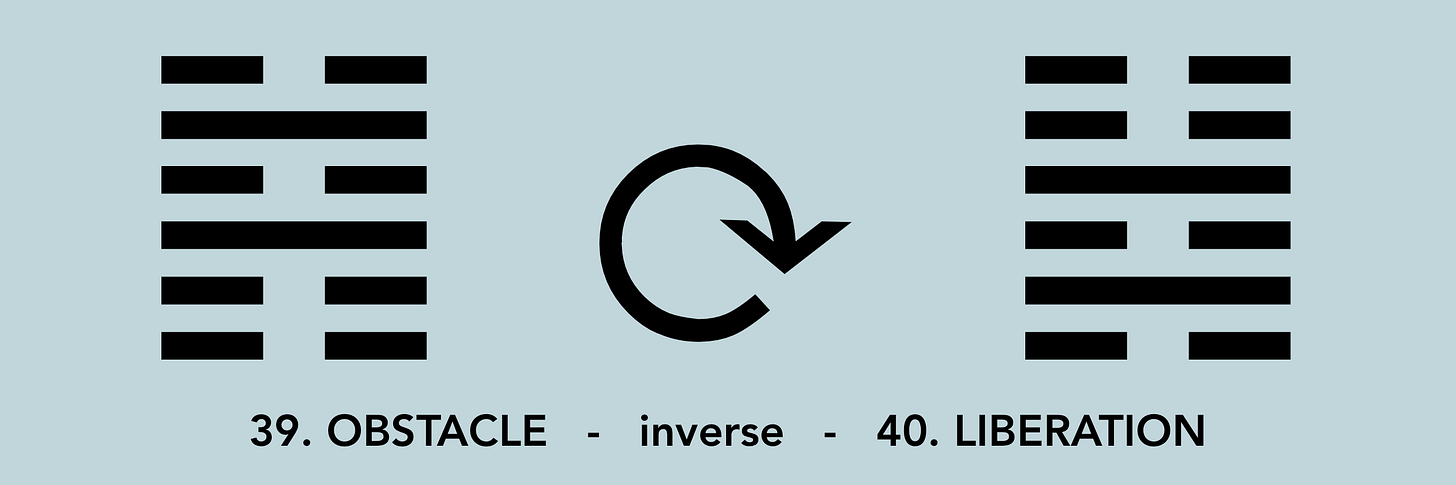

Remember, obstacles are there to be overcome. Without obstacles, life would also have no solutions. When the Obstacle hexagram is inverted the hexagram of Liberation appears. Now it is important, however, to make sure that in time liberation does not itself become the next obstacle.

I take people there, I take others back

My ferry is just about a sort of bridge

And if the ferry were as long as the width of the stream

Then it could stay put, an economist last told me

But that would be inconvenient for river traffic

So the ferry is short and goes back and forth

Then it goes out, then it docks, then it takes off again

…

The Ferry - drs P

At the time of the creation of the I Ching, China's great rivers already formed imposing barriers. In the north of the country flows the Huang He, the Yellow River, and in the south the Chiang Jiang or also Yangtze. In their upper reaches, the water is fierce and raging; their lower reaches are massive bodies of water. The crossing was no easy task, but as well for a potential conqueror. An obstacle to traveller and trade turned into a line of defence. Like Rhine and Danube once were for the Roman Empire. Or closer to home, the Dutch Waterline for the Dutch Republic.

A second appearance of Obstacle in ancient China was the Himalayas. Below Mountain and above Snow. Traditionally, travellers had to avoid the world's highest mountain range and, of necessity, had to make the long detour around it. Indian Buddhist monks undertook the trek on foot - westward and northward - to where Pakistan and Afghanistan now lie - encircling the unapproachable mountain giants. They traversed the corky Taklamakan - the ‘Enter and Never Return Dessert’ - do you know a more archetypal name for an obstacle? To eventually arrive at oases like Turpan and Dun Huang, stopping places on the Silk Roads, already well on their way toward the Chinese capital Chang'an.

Chinese monks on their way to India travelled the opposite way. An imaginative version of this phenomenon can be read in The Journey to the West, where monk Tang Sanzang along with, Sun Wu Kong, the Monkey King and their mates undertook this long dangerous journey around the Himalayas.

The figure of Tang Sanzang was based on the historical Xuan Zang (602-664), a Chinese monk, who completed the awe-inspiring walk twice. He left for India to make an in-depth study of Buddhism. After years, he returned to China taking with him a large number of Buddhist texts. The translation by him into Chinese marked the meeting of the two great Asian cultures.

A good fifteen years ago I visited the Wild Goose Pagoda near the then Chinese capital Chang'an, now Xi'an. The texts brought from India and translated by Xuan Zhang were kept in this monastery. That same year, a second trip took me to Nalanda on the other side, the south side, of the Himalayas. There, in northern India, stood the ancient Buddhist university, where Xuan Zang stayed and studied. These two places, separated by a huge mountain range, are intimately connected in history and culture by travellers like Xuan Zhang.