The text of this post has been translated from Dutch to English with DeepL. It will be manually edited and streamlined soon.

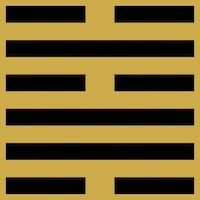

THE IMAGE of the two trigrams: below Wood, above Water. Plants absorbing water. Also: watering plants. A watering can. Irrigation.

Which is better? Pouring a big tub of water over parched soil, or watering that soil, misting it? Gardening is cultivation, is patience. Ultimately, the gardener - through the garden and gardening - cultivates himself.

The health of a nation reflects the health of its people. The health of the people in turn follows the vitality of the food - and thus of the land, of the earth. If the earth is impoverished and depleted - read Chapter 47. Exhaustion - then regeneration is called for. Regeneration in the big picture - but first and foremost in the small. The gardens of the future have existed for a long time, of course, but are no less inspiring and visionary for that.

The essay below was previously published in See All This 30 in Summer 2023.

GARDENS OF THE FUTURE

MAN’S CURIOSITY has always been limitless. It has driven him time and again to leave his familiar and ordered surroundings and enter the wilderness. Terra incognita held the promise of new and better living conditions. The attraction was evidently stronger than the deep-seated fear of the unknown or the wild.

These days, we venture into nature by hiking in the dunes, walking the dog in the woods, or heading into the mountains on holiday. However, one indispensable ingredient of wilderness – the possibility of getting lost – has now almost vanished. To truly get lost is no longer to know where you are or what to do. It means surrendering to what is to come, facing danger, and accepting an outcome that is uncertain. Our current nature excursions are safe and predictable. Paths, signposts and mobile navigation see to that. On a map of today’s Netherlands, the red colour of built-up areas predominates. Buildings, roads and streets, pipes and cables, fences and signs are everywhere. Real wilderness seems to have gone for good.

To imagine what was once there, I flip through the Atlas van Nederland in het Holoceen. From 9000 BC to more recent historical periods, its maps show a virtually untrodden land. Untamed rivers, a merciless sea, malarial swamps, marsh and dense forests. Except on the most recent maps of the atlas, there is little or no human presence and natural processes of accretion and decline take their course.

As man has cultivated every corner of the land, he has also domesticated himself. The wild natural landscape outside has been paved over and the wild inner nature suppressed, only rearing its head from time to time in a dream, in sex, or in a football stadium. Emma Marris opens her book Rambunctious Garden with the apt words:

‘We have lost a lot of nature in the past three hundred years – in both senses of the word lost. We have lost nature in the sense that much nature has been destroyed: where there was a tree, there is a house; where there was a creek, there is a pipe and a parking lot; where there were passenger pigeons and Steller’s sea cows, there are now skins and bones in dimly lit museum galleries. But we have also lost nature in another sense. We have misplaced it. We have hidden nature from ourselves.’

It is, of course, necessary to protecting what is rare and fragile. We have to build fences, set up signs and pass laws. But the resulting nature reserves become as untouchable as the collection pieces in a museum cabinet. The shielding of wild nature deprives us of our inner wildness.

Since we bought a house in Amsterdam-IJburg, we have left the modest front garden-cum-car park to itself. The previous owner had left some flowering plants, a rose bush and a shrub. After five years of rewilding, the original order of this new-build neighbourhood, has become overgrown and disappeared. We have not kept track of how many plant species have arrived by winf or had their seeds transported here by birds. In any case, there are an remarkable number of them. In the sunshine of early spring, there is a coming and going of bees, wasps and bumblebees. Kneeling down, you discover a miniature jungle.

This diversity contrasts sharply with the neighbour’s front garden, which consists of only two elements: paving slabs and a privet hedge. The whole thing looks uncluttered and is, so to speak, maintenance-free, and there is plenty of space to park the car and bikes. The two adjoining gardens represent two completely different world views.

When we moved into the house a few years ago, most of the leaves of the privet hedge separating the two gardens had been eaten away by weevils. A rather shabby sight. I understood that these beetles were feasting on garden shrubs all over the neighbourhood. Our neighbour’s method of pest control consisted of cutting away the affected leaves with scissors at regular intervals. He put the leaves in a plastic bag that went into the bin. Our approach was much less active. Leaving the garden to itself year after year increased the variety of plants and insects. The place gradually became a mini-oasis for birds (and cats). Greater biodiversity, even on this small scale, brings greater collective resistance and resilience.

This year, the privet hedge looks impeccable again: no trace of the weevils and clipped leaves. I assume the neighbour sees their disappearance as the triumph of his relentless cutting. I, on the other hand, see the rewilding on our side of the hedge as part of the solution. Yet I can hardly take pride in it. After all, it took no labour or skill: I was merely an observer.

The most important tool for establishing a garden is the courage to do nothing. All too often, the keen gardener has the urge to immediately start frantically working on his or her new plot of land. Plan, dig, stake, organise, select and weed. A feasible garden created in the image of the diligent gardener. Not that hard work and enjoying the labour of gardening is out of the question. But that work comes later. The first priority is to look closely, observe carefully, with all the senses. No special technique or prior knowledge is needed for this. The first and only real requirement is not to go straight into action, but to get acquainted with the earth and what lives and grows in it.

The original inhabitants of the garden are generally labelled weeds. They are usually not part of the gardener’s plan and need to be removed. Irritatingly, they keep popping up. In Weeds, Richard Mabey writes:

‘‘Plants become weeds when they obstruct our plans, or our tidy maps of the world. If you have no such plans or maps, they can appear as innocents, without stigma or blame ... The best-known and simplest definition is that a weed is a plant in the wrong place, that is, a plant growing where you would prefer other plants to grow, or sometimes no plants at all.’

Putting plans and frenzied labour aside for a moment frees weeds from the stigma of being ‘undesirable’. The weeds – pioneer plants that want to cover the surface of the garden and hold the earth together – tell us much about the state of the soil. They are indicators of its history, recent use, disturbances, over-fertilisation and the quality of soil life. The observant gardener is attentive to the weeds. Why does that particular species grow here and not there? What does the presence of another species mean for the condition of the soil? And what story is told by the way one kind of weed is succeeded by other species?

By seeing weeds not just as unwanted guests, you get a growing understanding of what is necessary and what is not. What to weed and what to leave. The complexity of cohesion within even the smallest garden is enormous and ungraspable. Understanding natural processes and coherence comes from direct observation, in bits and pieces. Instead of the gardener making the garden, the garden and its inhabitants take the leading role.

Observation is not limited to what grows on the earth, but also focuses on what lives within the soil. For part of the year, I live with my family in a cabin set in woodland beside the Vecht river. The land slopes gently away from the riverbank, a remnant of sand carried there over the centuries. Most of the oak trees around the house are relatively young, around 75 years old. The trees and undergrowth are home to a wide variety of living things. One spring morning a few years ago, we counted no fewer than 30 species of birds within an hour. Not bad for such a relatively young forest.

This woodland is a remnant of oak coppicing culture. For centuries, wood and bark were regularly extracted from it. For construction, for posts and poles, or to fuel stoves and ovens. But the most common activity was to produce tannin from the oak bark, used in tanning leather. The trunks were cut some way above the ground and new branches grew naturally from the remaining stumps. The woodland floor and the common root structure itself remained untouched. A visiting ecologist from Landschap Overijssel estimated the age of the root system at 600 years. All these centuries, the soil has remained free of spade and plough. The communal root system, the thick humus layer and an extremely diverse soil life have remained intact.

Soil life is an ecosystem in itself, a dark underground world with an endless number of larger, smaller and tiny creatures. Besides the unsurpassed mole and the indispensable earthworm, you will find mites, nematodes, springtails, spiders, centipedes, the most diverse strains of bacteria and protozoa. And between the countless plant roots and hair roots, there is a gossamer web of fungal threads (mycelium).

The hypha, the fungal threads, connect with the tree’s hair roots. The mycelium of the fungus (myco) and the root (rhiza) form a miraculous symbiosis: mycorrhyza. The fungus supplies moisture and nutrition to the tree and receives sugars in return. The already enormous range of the trees’ root system is thereby greatly increased. The mycelium also interconnects trees. This network, barely visible to the naked eye, is also known as the ‘wood wide web’. The knowledge of its existence blurs the conventional dividing lines that we unconsciously draw between different organisms and which have previously shaped our world-view.

But it is not only trees that live in symbiosis with fungi. Most plants do so, including garden plants. In a garden where the soil is not annually changed and disturbed, the complex of fungal cultures remains intact. In this sense, forest and garden are not essentially different. In a ‘forest garden’ or a ‘food forest’ (a garden inspired by the close-knit relationships within a healthy forest community), the soil retains its plant cover all year round. Planting is not confined to annual plants, which leave bare soil after harvesting especially if all the ‘weeds’ have been removed during the growing season – but prioritises perennial plants, which continuously root and cover the soil. Small plants, shrubs and trees complement each other, and the strict distinction between ‘herb and weed’ is blurred. Because there is no digging and ploughing, the soil structure improves and there is every opportunity for a rich soil life.

This type of garden is a paradise for different species of earthworms. A few hundred specimens per square metre is no exception. Charles Darwin’s last publication deals with the earthworm. He wrote:

‘It is doubtful whether there are many other animals that have played such an important role in world history.’ Aristotle considered earthworms ‘the bowels of the earth’.

How nice it is to have a garden where soil fertility recovers over the years and soil life becomes richer and richer.

A gardener who has the courage to step out of action mode and sometimes simply observe, might let some of the garden go feral. The contrast between the feral and the planned part of the garden is interesting, to say the least. The essence of ‘rewilding’ is to trust and observe natural processes. Scale is not an essential element. An organisation like Rewilding Europe shows that a return of wilderness in large areas is possible if the right conditions are created. Entire ecosystems recover; original flora and fauna return.

But the dynamics of a living wilderness can also show themselves in a corner of the garden or containers on the balcony. Last year, Dutch newspaper NRC wrote about De Wilde Tuin. In collaboration with Tilburg University, the newspaper invited readers to allow one square metre of their gardens to go back to nature and to monitor the process. The call resulted in 8,500 participants, many of whom reported on their observations. Their reports are testimonies to wonder and discovery, frustration and insight.

Compared with our world of mown lawns, conifer hedges, concrete slabs and gardens from which all wildness and life has been banished, the garden of the future will have immense diversity. We can find inspiration for it all around us. See the wonderful example set by nature photographer and filmmaker Ruurd Jelle van de Leij’s rewilding of a meadow in Friesland. Discover Martin Crawford’s 30-year-old food forest in Devon, England (see below). Or listen to Michael Pollans TEDtalk, in which he describes how the gardener makes the decision on selection and breeding, but the plant leads him to do so and is the actual initiator.

Let Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg show you how to see the garden from the perspective of pollinators. And how about the Los Angeles garden of guerilla gardener’ Ron Finley? See William Sallatin’s Polyface Farms website, a compelling example of regenerative horticulture in Virginia. Or the Bodemzicht project near Nijmegen. Be sure to watch the inspiring documentary Onder het Maaiveld (Below Ground Level) on the restoration of soil life. Or visit the Garden Futures: Designing with Nature exhibition at the Vitra Design Museum in Weil am Rhein, and get to know Jamaica Kincaid’s garden, full of stories and history. The garden of the future and the gardener of the future will mirror each other in organisation, in wildness and in diversity.