THE IMAGE of the two trigrams: above the Earth, below a Lake. A deepening in the Earth's surface. Water has gathered in this, as it always seeks the lowest place. Water conforms exactly to the receiving form of the earth. Like wine to the bottle, tea to the glass. Is a more perfect rapprochement possible?

Within the family of eight trigrams, Earth represents the mother, and the Lake represents the youngest daughter. A lake in the womb of Mother Earth. The image of embrace and closeness.

This post has been translated from Dutch into English with DeepL. It will be manually edited and streamlined soon.

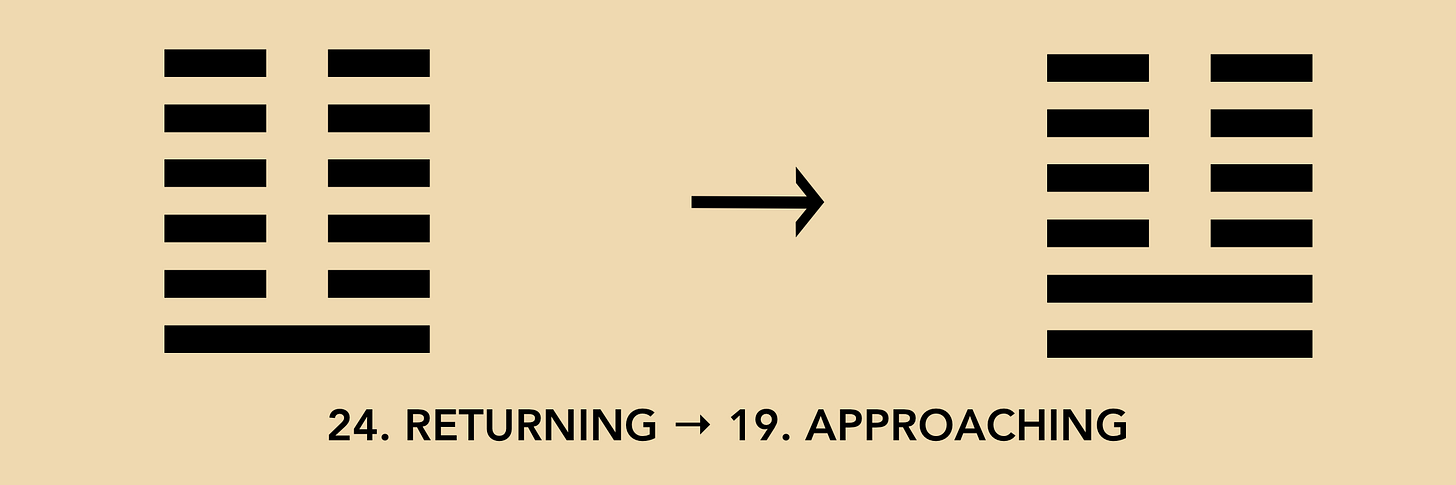

And the image of whole hexagram? Two active lines push up from below. That outlines a continuation of the situation of 24. Return, where a single line, tentative and still hesitant, creeps up. Chapter 24. Returning marks the darkest phase, a time without hope, worse it could not be. However, in the depths, in the hidden, opportunities turn. Read also:

The return of the first line meant nothing less than a revolution. Not much could be seen on the outside yet. It was waiting for a perpetuation, it just takes a bit of time. After the pioneer come the trend followers. After the long-awaited turnaround comes the follow-through, the rapprochement, the arrival.

The plane has just landed and immediately there is the inevitable welcome message. Safe landing, hold on to your seatbelts, be patient and stay put for a while, and: we have arrived at Schiphol Airport. How liberating it would be, if the steward or stewardess would stick to: you have arrived. Point. You've arrived, you're here, finally at your destination, you don't have to go any further. You can still travel again after this landing, but you don't have to. The purser's simple words could so break the FOMO curse. So that travelling becomes a possibility again, not a reflex.

All that remains is to neutralise the FOBO (Fear Of Better Options), the ROMO (Rage Of Missing Out), the YOLO (You Only Live Once), the FONK (Fear Of Not Knowing) and the FOLO (Fear Of Looking Old), and it will be very quiet at Schiphol Airport.

At the time, on the verge of the entrance to the small village of the late Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh, there was a sign saying 'Village des Pruniers'. And underneath it 'tu es arrivé'. At first glance, a thoughtful gesture to welcome all those who had undertaken the short or longer journey to the village in the south-west of France. It took some time for the deeper layer beneath the simple text to reveal itself. In daily intercourse in the small community, visitors and permanent residents were time after time reminded that there was no reason to rush or act out. Or to pretend otherwise, to achieve something, other than to dwell in the here-and-now. Tu es arrivé.

Without the unexpected wish of the purser, without the priceless memory on the small village welcome board, life is likely to remain stuck in a perpetual preparation phase. So when does life finally begin? After graduation? After finding the ideal partner? After a few more ticks on the bucket list? Maybe as early as tomorrow? Or after some more preparation?

I led a life as a travelling artist, dealer in storytelling and chi kung choreography. Amsterdam during the week and once or twice a month for a long weekend on the road. By plane to one of the other capitals of the old continent: Vienna, London, Lisbon. I knew the best bakeries and breakfast places in Basel and Zürich, Munich and Hamburg, Pisa and Helsinki. Arriving somewhere simply takes time, and if you are not careful, arriving merges with departing and travelling turns into a mess. So much for Europe, in between Asia pulled like a magnet. Marco Polo modestly limited himself to a single trip in his lifetime, now you hop back and forth for a few days to test out the best noodles and kimchi in Seoul or take a few selfies on the Wall.

One languid afternoon in the hammock, I made a paper list of all the films I ever saw. And on a winter evening by the stove, something similar, about all the books I ever opened and read. The only sense it made was the realisation, it was a lot.

Looking back over the years of moving a lot, I counted 259 trips outside the Dutch borders.

Until just under a decade ago, after a diagnosis of a chronic neurological condition, the turnaround set in. First reluctantly, hesitantly and reluctantly, I said goodbye to Schiphol. The radius of my movements shrank radically. What I had to learn was to arrive without travelling. To move without leaving.

The scale of the map I navigated on, like many of my contemporaries, was 1:100,000,000. Breakfast in Vienna, a meeting in Hamburg, classes in Shanghai, before you know it you feel like an up-and-coming European or a citizen of the world. The scale was impressive, the whole world was depicted, but I must confess, on such a map, the perception is thin and vague.

This strikes me as one of those marvellous contradictions that the Book of Change tries to lay out. The scale of the map and the intensity of experience are inversely proportional. Didn't Lao Zi already write: 'The further you go, the less you know'? I therefore traded in the world map for a 1,25,000 map and the distant journeys transformed into micro-adventures.

Read also:

Our house and its immediate surroundings, the green Salland countryside, seemed far from spectacular. The real adventure, wild nature was not to be found there. Since then, I exchanged plane, train and car for bicycle and walking. I just went along with the inertia my health commanded me. Eight winds turned out to be a thousand. Initially, only roads and streets were marked on the map, the winding line of the river, and railway, houses and villages and an occasional town. By staying close by, going slowly, looking more closely every day and 'the importance of being amazed about absolutely everything', the map has filled up day by day. Stories, history, geology, plants and animals, residents and passers-by, yes whatnot, have taken their place.

Let me give the word to Alastair Humphreys, a micro-adventure specialist. Years of travel, adventure, and exploration had taken him to the unlikeliest places on earth, from the tropics to the poles, from the seas to the high mountains. But then he came to realise that constant travelling and the decay of nature, changing climate, were at odds with each other.

If I love wild places so much, I’ve begun to wonder, am I willing to _not_ visit them in order to help protect them?

The arrival of children gives the final push: where do I find adventure around the corner?

I felt a need to reconcile my enthusiasm for exploration with my decidedly unadventurous local environments. One morning I set down a heavy laundry basket on top of piles of homework scattered over the kitchen table, carried a pair of abandoned cereal bowls to the dishwasher, and wondered: What if this bog-standard corner of England was actually full of surprises if only I bothered to go out and look? Maybe the things I’ve chased from India to Iceland — adventure, nature, wildness, surprises, silence, perspective — were here too?

What follows is an encounter of the surroundings of the Vinex-wijk, the soulless suburb, the cluttered no man's land between the city and the countryside. Exit roads, LED lighting, business block boxes, high-voltage cables, larded with indistinct remaining greenery. No meat and no fish, unnamed, unloved.

As Robert Macfarlane wrote in Landmarks, 'Language deficit leads to attention deficit. As we further deplete our ability to name, describe and figure particular aspects of our places, our competence for understanding and imagining possible relationships with non-human nature is correspondingly depleted.'

Each week, I decided, I would explore one of those squares in detail (de vierkanten van het coördinatenstelssel van de stafkaart die hij van het gebied kocht), doing my best to see everything there, to walk or cycle every footpath and street, and to learn as much as I could along the way. I wanted it to be serendipitous, not governed by my preferences. I hoped to see things I would not ordinarily come across. I decided to treat everything as interesting. The late Terry Pratchett once gave a lecture on 'the importance of being amazed about absolutely everything,' which felt like a fitting mission statement.

A single small map is enough for a lifetime - Alastair Humphreys

I see, I foresee, a map even finer than the plan, than the treasure map. Lewis Carroll already described it in Sylvie and Bruno: the 1:1 map. Jorge Luis Borges picked up the idea in On Exactitude in Science and Umberto Eco in How to Travel with a Salmon.

‘What a useful thing a pocket-map is!’ I remarked.

’That’s another thing we’ve learned from your Nation,’ said Mein Herr, ‘map-making. But we’ve carried it much further than you. What do you consider the largest map that would be really useful?’

’About six inches to the mile.’

’Only six inches!’ exclaimed Mein Herr. ‘We very soon got to six yards to the mile. Then we tried a hundred yards to the mile. And then came the grandest idea of all ! We actually made a map of the country, on the scale of a mile to the mile!’

’Have you used it much?’ I enquired.

’It has never been spread out, yet,’ said Mein Herr: ‘the farmers objected: they said it would cover the whole country, and shut out the sunlight ! So we now use the country itself, as its own map, and I assure you it does nearly as well.’

Sylvie and Bruno - Lewis Carroll

A map where as much is inscribed as can be found on the surface of the earth. But what to do with the depth and height, with the life hiding from view in the soil and with all the life above, in the atmosphere. I close my eyes and see a 3D map, as full and rich as the earth itself. Michael Ende wrote about this amazing phenomenon in Momo.

Guido, incidentally, had never told the same story twice since Momo’s arrival on the scene; he would have found that far too boring. When Momo was in the audience a floodgate seemed to open inside him, releasing a torrent of new ideas that bubbled forth without his ever having to think twice.

On the contrary, he often had to restrain himself from going too far, as he did the day his services were enlisted by two elderly American ladies whose blood he curdled with the following tale: ‘It is, of course, common knowledge, even in your own fair, freedom-loving land, dear ladies, that the cruel tyrant Marxentius Communis, nicknamed ‘the Red’, resolved to mould the world to fit his own ideas. Try as he might, however, he found that people refused to change their ways and remained much the same as they always had been. Towards the end of his life, Marxentius Communis went mad. The ancient world had no psychiatrists capable of curing such mental disorders, as I’m sure you know, so the tyrant continued to rave unchecked. He eventually took it into his head to leave the existing world to its own devices and create a brand-new world of his own.

He therefore decreed the construction of a globe exactly the same size as the old one, complete with perfect replicas of everything in it — every building and tree, every mountain, river and sea. The entire population of the earth was compelled, on pain of death, to assist in this vast project.

First they built the base on which the huge new globe would rest — and the remains of that base, dear ladies, are what you now see before you.

Then they started to construct the globe itself, a gigantic sphere as big as the earth. Once this sphere had been completed, it was furnished with perfect copies of everything on earth.

The sphere used up vast quantities of building materials, of course, and these could be taken only from the earth itself. So the earth got smaller and smaller while the sphere got bigger and bigger.

By the time the new world was finished, every last little scrap of the old world had been carted away. What was more, the whole of mankind had naturally been obliged to move to the new world because the old one was all used up. When it dawned on Marxentius Communis that, despite all his efforts, everything was just as it had been, he buried his head in his toga and tottered off. Where to, no one knows.

So you see, ladies, this craterlike depression in the ruins before you used to be the dividing line between the old world and the new. In other words, you must picture everything upside down.’

The American dowagers turned pale, and one of them said in a quavering voice, ‘But what became of Marxentius Communis’s world?’

’Why, you’re standing on it right now,’ Guido told her. ‘Our world, ladies, is his!’ The two old things let out a squawk of terror and took to their heels. This time, Guido held out his cap in vain.

Momo - Michael Ende

To be continued: