Below is the end-to-end rewritten version of the article published last May. It has been translated from Dutch into English with DeepL. It will be manually edited and streamlined soon.

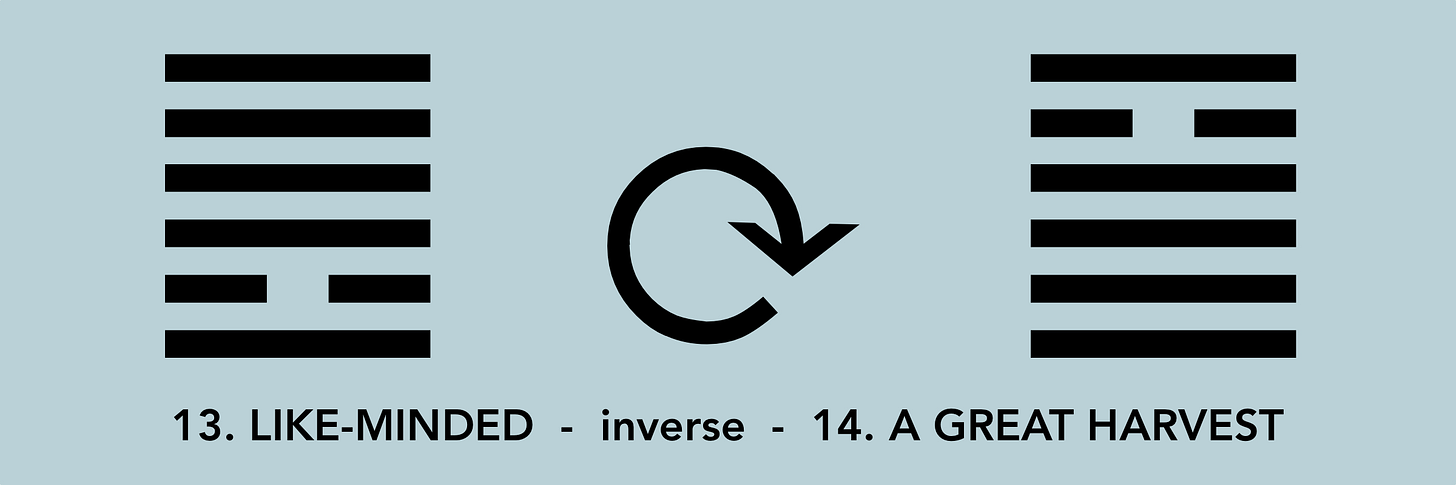

THE VIEW of two trigrams: below Fire, above Heaven. The sun shines on the earth and from its surface heat rises. Thermals carry water vapour, which, when enough altitude is reached, condenses and form clouds. The energy released from this further amplifies the thrust.

Is there anything more impressive than seeing clouds expanding in slow motion? Boring? Nothing special? You can save yourself a trip to the mountains, and just stay home. Look up, imposing mountain formations float past you. On the cloud front, no day is the same. Marvel at modest pile clouds, the cumulus humilis. Or at the stack of an imposing cumulus congestus. And then, at the end of a hot summer day, higher than a Himalayan giant, the awe-inspiring cumulonimbus.

On the inside it contracts, on the outside it ferments, swells, expands. Fire below, Heaven above: the image of Like -minded and Community.

Pushing each other, a cumulative culture, ideas generating ideas. Passing on experiences, misses and inventions. Standing on the shoulders of someone, who in turn also stands on the shoulders of another.

The image of the next chapter 14. A Great Harvest is exactly the opposite: above Fire, below Heaven. Here, the sun is high in the sky and its rays shine on the earth. Everything that lives receives light and warmth. And at the end there is a great harvest.

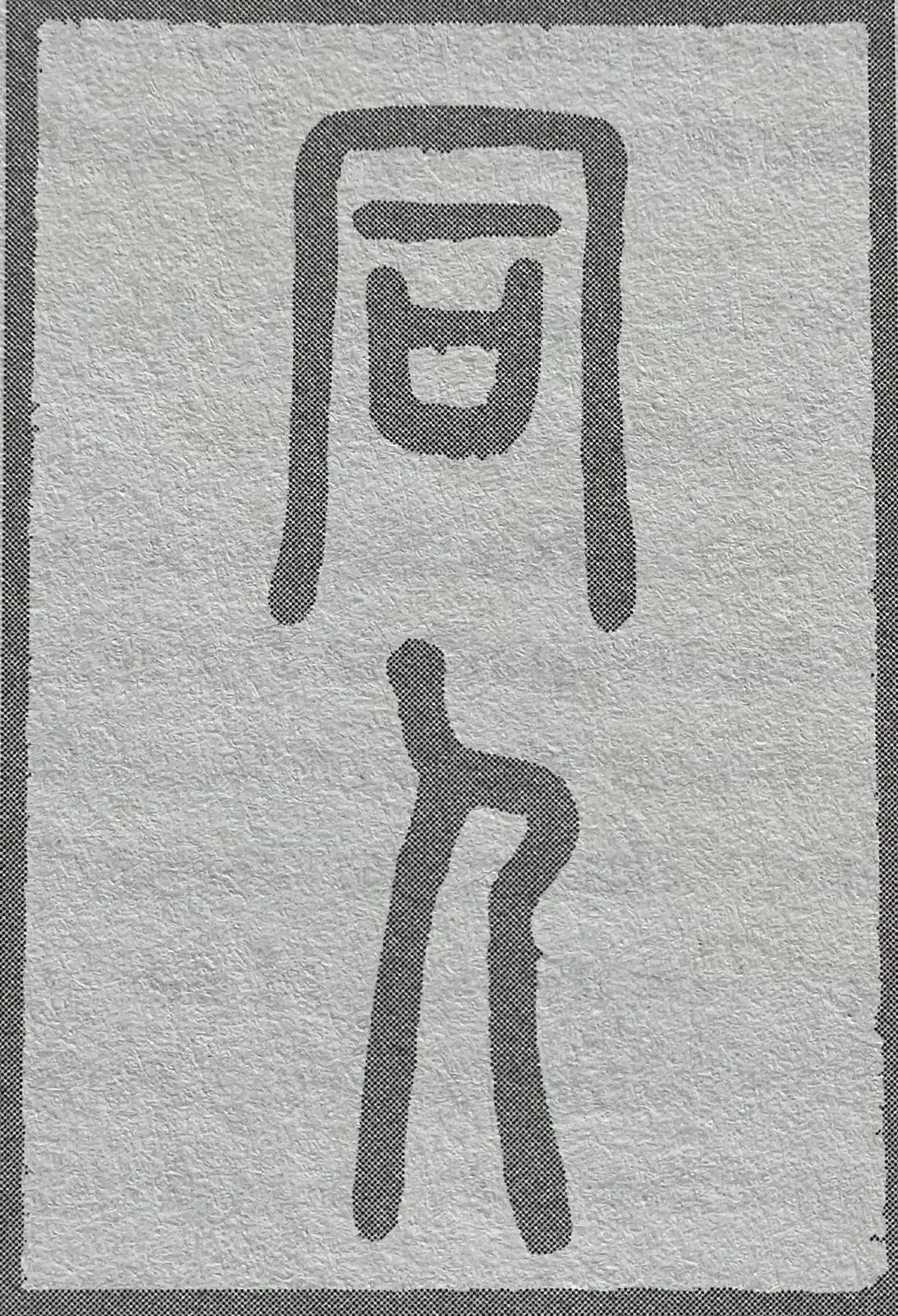

The top character is called 'tong'. The three lines forming a standing rectangle refer to a door or a house. Within that, a single horizontal line: the number one. And a square symbolising mouth. The bottom character, 'ren', means 'human'. Taken together, this denotes a group of people speaking with one mouth. A community, a group with a strong connection.

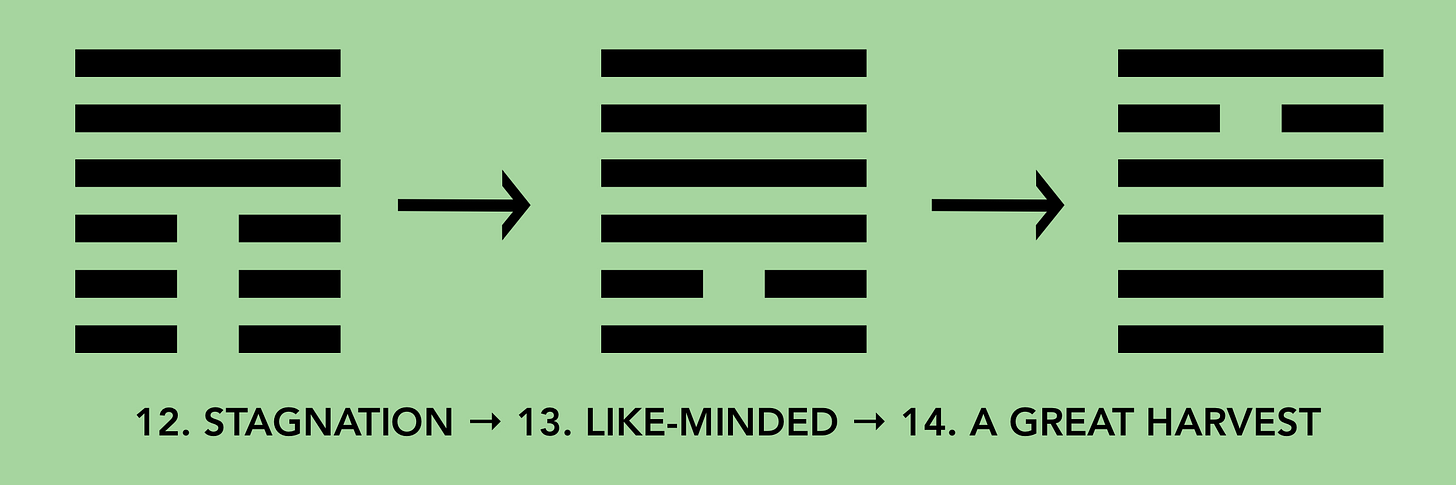

Chapter 13. Like-minded follows Chapter 12. Stagnation. The hexagram of Stagnation is clear: it consists of three broken lines below, and three solid lines above. Heaven above Earth. At first glance, this seems like the perfect configuration, everything is in its designated place. Until you realise that the situation described therefore lacks all momentum. Heaven moves upwards, but was already at the top. Earth moves down, but was already there. Heaven and Earth are separating, there is alienation and a status quo. The rich getting richer and the poor getting poorer. The appropriate response when life is stagnant lies in seeking like-minded people and forging coalitions. Cooperation is always the winning strategy in human development, especially in times of stagnation.

First, take a good look at how the other person handles it. Ah, so that's how you do it. Or, precisely not that way at all. You might as well turn a bad example to your advantage. Imitation is the way - imitate, duplicate, repeat, copy-cat, emulate - to possibly add something of your own later. Better to copy well than invent badly. Look well, then imitate and improve a little each time.

Isn't it curious that we still frenetically try to teach our children something completely different. While our culture is built on learning by copying each other, adopting each other's inventions and working closely together, cheating during school is a mortal sin. If you get caught doing it during an exam, you hang. After all, you are expected to dig up the question from your own memory and formulate it in your own words. And above all, not to look around to see what others are putting down. A catch-22 between cumulative culture and individualism.

The all-consuming obsession with originality clashes with the need to cooperate. Children are being groomed for a life in a society, which is shuttered with copyright, patents, and property rights.

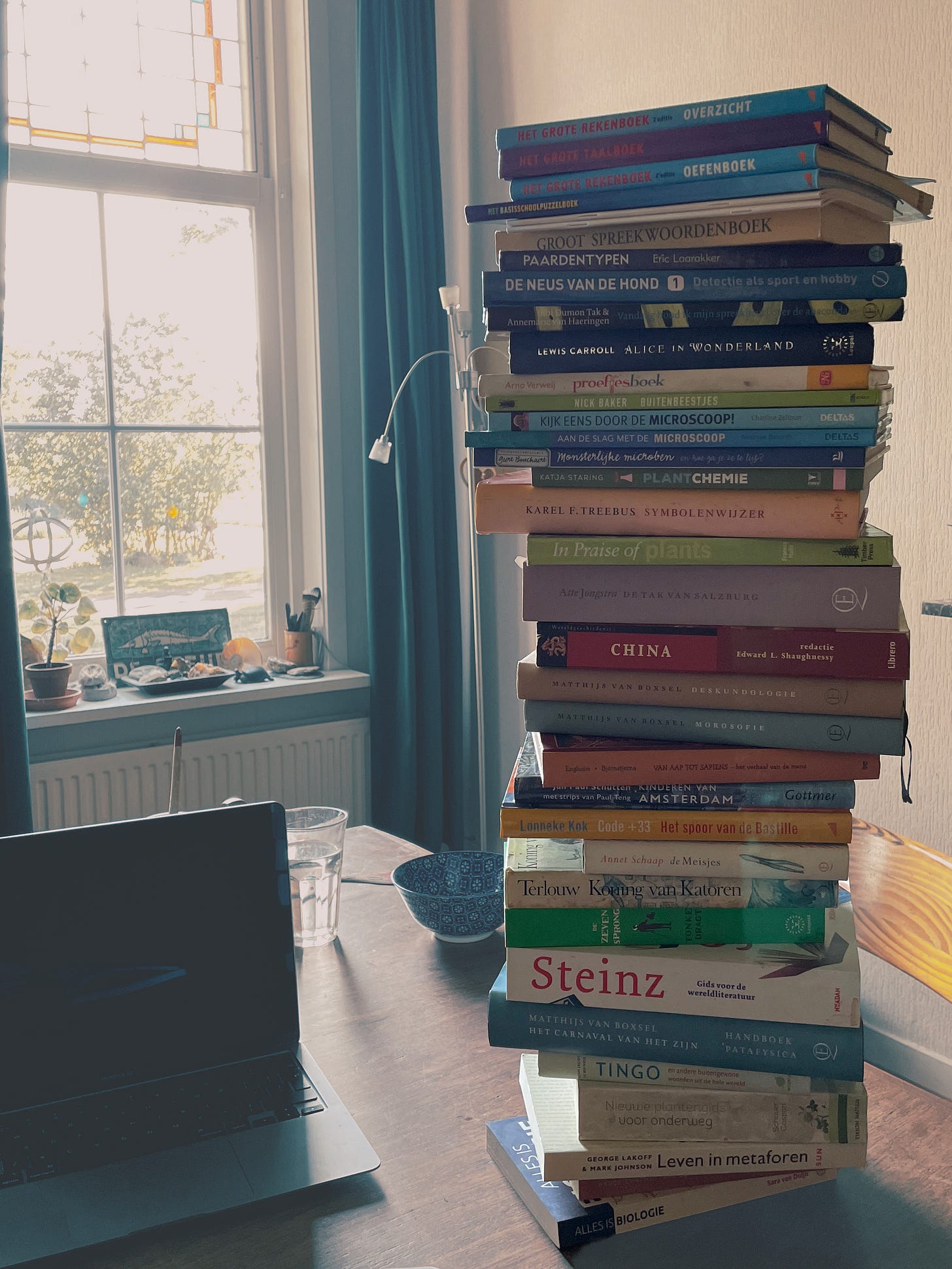

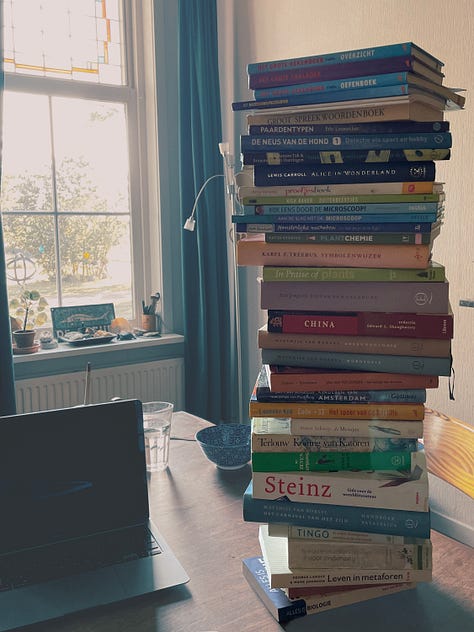

How easily a writer is influenced by what he reads himself. A keen insight, a knack with words or sentence structure, pace or tone, they are involuntarily transferred to the text to be written. Anyway, the writer is surely aware of this induction when the reading and the writing are close enough in time. What no longer lies atop the pile of memory, and from which unconsciously plenty is drawn, are all those books and newspapers he once, in the distant past, read. Opinion pieces, articles and instructions for use, labels on jars, subtitles and advertisements. Relevant or futile, high literature or juice, it has all entered, and if it hasn't left again, it has undoubtedly nestled itself somewhere in the inner self.

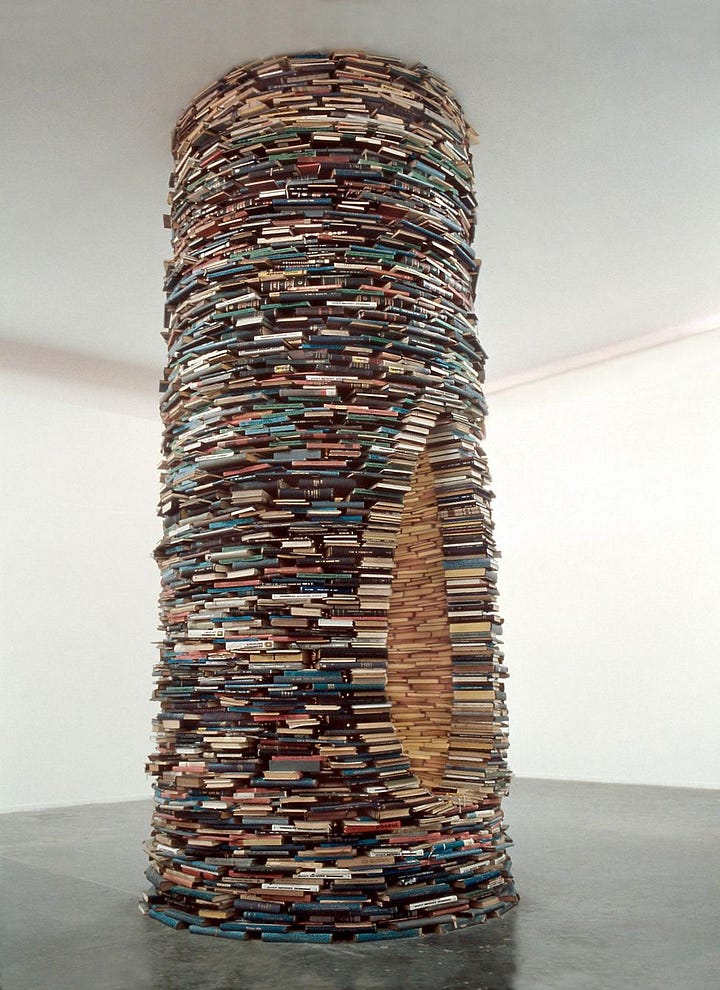

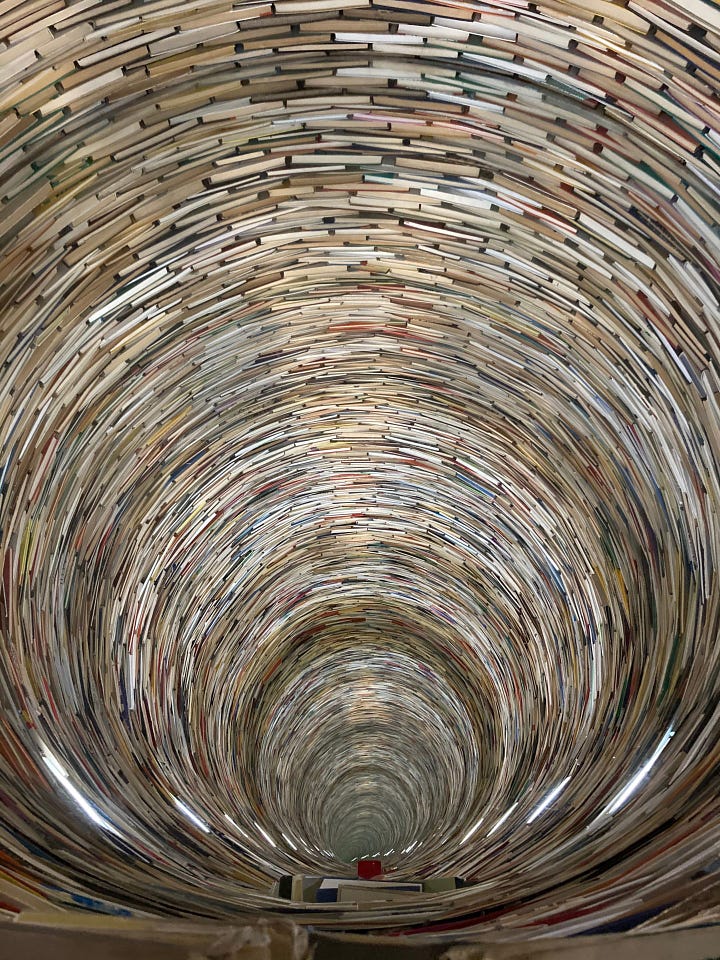

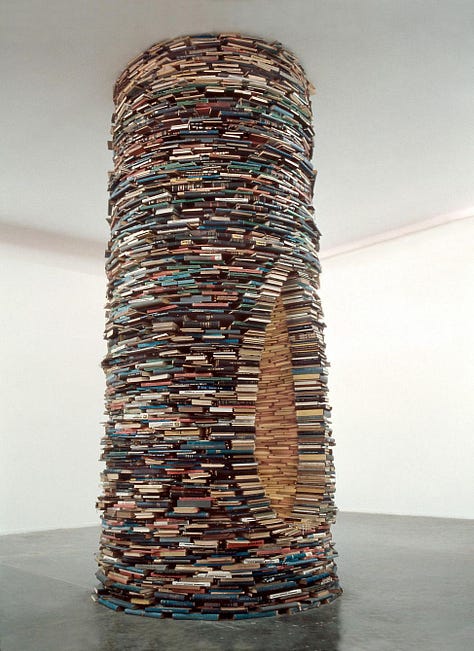

Imagine all you ever read. Racked up. Stacked up. A cumulonimbus thunderstorm cloud easily reaches ten kilometres high. How high does your mountain of books, the dump of all the words you read, reach?

Depending on whether you are an avid or modest reader: between 20,000 and 50,000 words a day, in the form of books, newspapers, online text, emails, apps and posts, labels, advertising, subtitles, etc. A conservative average? 30.000? Per year, then, that becomes 365 x 30,000: around 11 million words. And on a reading life of 75 years: 825 million words.

So what is truly original, if thinking and writing is infused with the words and ideas of others? What belongs to whom? Who made up what? And the loathed and embraced AI writing assistant is not making all this any easier. Robotisation chased workers out of the factory and we can expect AI to take over much of the writer's work. Writers unite!!! We can't let that happen. At the same time, the rise of AI exposes the self-evident individuality of the writer. His name appears above the article and on the spine of the book, thereby taking possession of what is written. A fence with a sign indicating who owns this piece of the world of words and ideas. Maintaining the illusion that the writer is the creator. This is how it has been for the last few centuries. Authorship as a fence around a garden of ideas, with signs like 'private property' and 'forbidden to pick and take anything'. A book as a rectangular demarcation, a writers' landscape full of fences.

Remove the fencing around and within this short article: the writer fades and his community, his surroundings, take on colour. The Wavewatcher's Companion by Gavin Pretor-Pinney and the Cloud Appreciation Society, the only club I am happy to remain a member of for the rest of my life. Richard Wilhelm's I Ching translation, and Alfred Huang's, not to mention Deng Ming Dao's. And the commentary on it, for teenagers, by Julie Tallard Johnson. The faculty of geography at the University of Amsterdam, where I was introduced to the science of weather and cartography. The liberating lectures on the allowance of making mistakes by Sir Ken Robinson. The stacking and structure of 'Steinz, guide to world literature' and the many other books in the stack in the picture. Perplexity for the effortless calculation of the number of words to read in a lifetime. 'AI Signals the Death of the Author' by David Gunkel. And not to forget Miss Bijl from the primary school, who taught us how to write giant letters in the air. Jan Hupkes, the French teacher, who refused to use a textbook in class but instead just told stories, in French. And Willem de Ridder who always urged us not to forget that for the story, the listener is at least as important as the storyteller. Marten Minkema, Joe Perra, Sarah de Monchy for making the ordinary special. And Billy Collins and A.L. Snijders for their humorous lessons in brevity. To reiterate: what can you do without like-minded people?

To be continued in: